Module 1: Price’s Symphony No. 1 in E Minor

CREDIT G. NELIDOFF / SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS LIBRARIES, FAYETTEVILLE HTTP://BIT.LY/2JWKZRO

Module Introduction

By 1931, Florence B. Price lived in Chicago, divorced and independent, and composing seriously for the first time since college. Although she had written numerous children’s and practice pieces for her piano students in Arkansas, Price only turned to composing major orchestral works relatively late in life, when she was in her mid-forties. Her Symphony No. 1 in E Minor became her first big success. She wrote the majority of her symphony in 1931, finding humor and serendipity in an accident when she wrote to a friend, “I found it possible to snatch a few precious days in the month of January in which to write undisturbed. But, oh dear me, when shall I ever be so fortunate again as to break a foot.” The resulting piece was well received nationwide, granting Price a degree of legitimacy that encouraged her to continue writing major orchestral works. Three more symphonies, three concertos, assorted smaller orchestral works, and more than one hundred songs would follow the moment when Price found a powerful public stage for her pieces at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933.

The Symphony

Price’s Symphony No. 1 in E Minor consists of four movements. The first, Allegro non troppo, is in traditional sonata form and that lasts nearly fifteen minutes. This movement deliberately hearkens to Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony No.9 “From the New World”—a self-conscious nod to newly solidified conventions in the American orchestral sound and a claim on ten part of Price to being an integral part of this new, national symphonic tradition. The second movement, Largo, is a ten-part brass choir playing a newly composed hymn, accompanied by drumming. The third movement is notable for its expressive name, “Juba Dance,” which evokes an African-derived folk dance that was popular among slaves in the antebellum South, and for its brevity—the movement does not last four minutes. Price plays here with the expectation of a dance as the third movement of a classical symphony (which in European symphonies is often a minuet) and explores an African American musical style anchored in the South of the United States. Its concise format allows it to pass for a work of popular music. The last movement, Finale, is a fast movement of about five minutes in the form of a modified rondo. The use of the pentatonic scale, vital to African American musical idioms such as jazz and blues, is prominent throughout the work.

Initial Reception of the Symphony

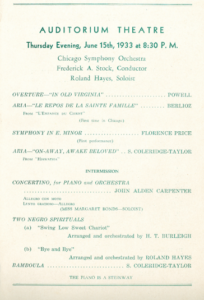

In 1932, Price entered her symphony into the national Rodman Wanamaker composition competition and won the prize for the symphonic category—a great honor that brought her national attention. This award attracted the interest of Frederick Stock, conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Stock and his orchestra premiered the piece on June 15, 1933, at the Chicago World’s Fair, as part of a concert dedicated to “The Negro in Music.” This was the first performance of a symphony written by an African American woman ever to be performed by a major symphony orchestra. Both Black newspapers—such as the Chicago Defender—and the White press, including the Chicago Daily News, sung the symphony’s praises. Her success spurred Price to greater ambitions. She sent scores and letters to conductors of prestigious orchestras, most notably Serge Koussevitzky of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, trying to get her work performed, but had little luck outside Chicago.

The 1933 Chicago World’s Fair

Given the motto, “A Century of Progress,” the World’s Fair: Columbian Exposition in Chicago took place from May to November 1933 and, again, from May to October 1934. It marked the 150-year anniversary of the founding of Chicago. Plans for the massive Exposition began before the stock market crash of 1929 that catalyzed the Great Depression, but despite the myriad hardships many Americans faced during this time, the Fair proceeded more or less as planned. The boisterously successful Fair became a symbol of hope for American progress and recovery in the midst of economic turmoil and national crisis. The African American community of Chicago fought hard to be involved with the Fair, seeing it as an opportunity to promote their artistic and historical accomplishments. Despite discriminatory practices at the 1933 Exposition that led some in Chicago’s Black community to boycott the Fair, the NAACP successfully lobbied for state legislation to bar racial discrimination from the 1934 Fair.

Nationalist and African American Vernacular Influences

Price’s compositional style is distinctive, and she took inspiration from a variety of elements. Her training at the New England Conservatory by George Chadwick familiarized her with the compositional style of Antonín Dvořák. This Czech composer had set the standard for American-style symphonic texture by taking inspiration from African American spirituals and Native American folk song, most famously in his Symphony No. 9 “From the New World.” Price’s teacher, Chadwick, was a member of the “Boston Six” cohort of American nationalist composers who continued to develop what became the quintessential American orchestral sound of the early twentieth century. He encouraged Price to explore the use of spirituals and other African American musical idioms in her compositions. Price seemed particularly fond of the Juba dance, which appeared not only in her first but also her third symphonies.

Performance History

After its premier in 1933, Price’s Symphony No. 1 was performed infrequently. What might have contributed to this neglect is the fact that the Symphony was not published until 2008; all previous performances relied on manuscripts and photostats. Price’s Symphony has recently enjoyed new popularity among American orchestras. Whereas the symphony was known to have only two performances in 2018, in 2019 the Symphony (or excerpts of the Symphony) were performed seventy-one times by orchestras across the country, including the National Symphony Orchestra. In 2020, sixty-two performances were planned, though many were canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Primary Sources

Brascher, Nahum Daniel. “Roland Hayes.” Chicago Defender, June 24, 1933.

CSO Sounds and Stories. “125 Moments: 072 Price’s Symphony in E Minor.” Last modified May 5, 2016. Accessed October 4, 2020. https://csosoundsandstories.org/125-moments-072-prices-symphony-in-e-minor/.

George, Maude Roberts. “Wanamaker Awards Given in Music.” Chicago Defender, October 1,1932.

Price, Florence Beatrice Smith, letter to Serge Koussevitzky, July 5, 1943. Library of Congress, Music Division.

Price, Florence. Symphonies Nos. 1 and 3. Edited by Rae Linda Brown and Wayne Shirley. Middleton, WI: Published for the American Musicological Society by A-R Editions, 2008.

Stinson, Eugene. Chicago Daily News, June 16, 1933.

Secondary Sources

Brown, Rae Linda. “Florence B. Price’s ‘Negro Symphony.’” In Temples for Tomorrow: Looking Back at the Harlem Renaissance, edited by Geneviève Fabre and Michel Feith, 84-98. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Price, Florence. Symphonies Nos. 1 and 4. Conducted by John Jeter. Recorded with the Fort Smith Symphony, May 13-14, 2018. Naxos 8.559827, 2019. CD.

Reed, Christopher Robert. “The Rise of Black Chicago’s Culturati: Intellectuals, Authors, Artists, and Patrons, 1893-1930.” In Roots of the Black Chicago Renaissance: New Negro Writers, Artists, and Intellectuals, 1893-1930, edited by Richard A. Courage and Christopher Robert Reed, 22-42. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020.

Rydell, Robert W. “Century of Progress Exposition.” The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society, 2005. Accessed September 26, 2020. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/225.html.

Wise Music Classical. “Florence Price Symphony No. 1 in E Minor (1932).” Accessed September 28, 2020. https://www.wisemusicclassical.com/work/58893/Symphony-No- 1-in-E-minor–Florence-Price/.

Investigations

Listening:

In the period from the late nineteenth century through World War II, composers from across the country were involved in a sort of artistic arms race for the “Great American Symphony,” a drive to develop a uniquely American contribution to this traditionally European genre. Florence Price’s Symphony No. 1 in E Minor made her a contender in this fight. Compare this Symphony other landmarks in the genre such as Amy Beach’s Gaelic Symphony, William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony, Roy Harris’s Symphony No. 4, or Aaron Copland’s Symphony No. 3. What strategies do the composers use to represent nation (Americanness) in these works?

Research:

Consult the 1933 World’s Fair concert program, and conduct some research on the performers and composers who were featured alongside Price at that World Fair concert in 1933. You will find, for example, that one of the other composers on the program, John Powell, was a staunch White supremacist who lobbied for Jim Crow legislation. What does the concert program say about the representation of music by people of color during this period?

Critical Thinking:

- This symphony was the first symphony by an African American woman performed by a major U.S. symphony orchestra, and it was well received at its premiere. Price was also a fairly prolific composer who traveled in the same circles as the Boston Six nationalists, and some of the most important figures of the Chicago Black Renaissance, as you will see in Module 2 below. Yet despite Price’s accomplishments and artistic pedigree, her symphony was little performed prior to 2019 and is rarely taught in music schools. What do you consider are the barriers to this piece’s, and Price’s, inclusion in the Western classical-music canon?

- What is a World’s Fair and what is its purpose? How does a concert dedicated to “The Negro in Music” fit into that purpose?