Module 2: Price’s Art Songs

Module Introduction

Module Introduction

In this module, we focus on Price’s songs in the contexts of prevailing power structures and networks of creative communities in order to explore how her music was created and spread. While Price used many musical forms, her songs are among the most collaborative ones. They demonstrate how different facets of her identity placed her in social structures which affected her career. Price worked with numerous distinguished artists like singer Marian Anderson, choreographer Katherine Dunham, and poet Langston Hughes.

National Reach

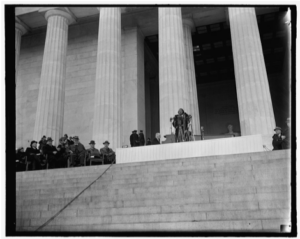

Surrounded by microphone stands in front of a crowd of 75,000, Marian Anderson sang on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday 1939. The last song on the program was Florence Price’s arrangement of the spiritual “My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord.” Anderson performed at the Lincoln Memorial because she was blocked by the Daughters of the American Revolution from a scheduled performance at Constitution Hall based on the fact that she was Black. In closing the program with a song written by a Black female composer, Anderson made a statement about racial equality and presented Price’s music to a larger audience. Anderson’s performance would make way for further progress against segregation and discrimination in the years following. For further context, it would be almost a quarter of a century before Martin Luther King would stand on the same steps of the Lincoln Memorial to deliver his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Spirituals and Black Performance

Price arranged spirituals for singing and incorporated spiritual melodies into some of her instrumental music. Spirituals are African American vernacular songs with texts based in Christian religious thought. Listeners at the time perceived spirituals as authentic musical expression of the antebellum South and a true form of American folk song. Like Anderson, other African American singers in the twentieth century embraced the popularity of spirituals, incorporating them into their concert performances along with Western classical repertoire.

Local Influence: The Chicago Black Renaissance

Like the African American arts communities in New York forming the better-known Harlem Renaissance, another community in Chicago flourished after World War I when the city saw an influx of Black residents during the main years of the Great Migration (1916-1918), and a vibrant arts and intelligentsia community rose even amidst the struggles of the Great Depression (through the 1930s). The city became a hotspot of culture during the “Jazz Age of the 1920s.” It became the birthplace of a rich artistic community that began in the 1910s but saw its greatest period of recognition in the late 1920s and 1930s, spearheaded by the literary works of Richard Wright. 1927 was an especially important year, which saw the Negro in Art Week exhibition held at the Chicago Art Institute, celebrating Chicago’s rich African American cultural life. Notable figures associated with the Chicago Black Renaissance spanned the arts, including writers (Arna Bontemps, Margaret Walker, and Gwendolyn Brooks), visual artists (William Edouard Scott, Charles White, Archibald John Motley, Jr., and Eldzier Cortor), gospel and jazz figures (Thomas A. Dorsey, Mahalia Jackson, and Louis Armstrong), and choreographer Katherine Dunham. In fact, Price wrote the music for Dunham’s concert dance, Fantasie Nègre, in 1936. Price traveled in the same circles as many influential Chicago writers and performing artists who encouraged and influenced her work.

Price’s Networks

In Chicago, Price was connected to additional Black social networks that supported her work like the R. Nathaniel Dett Club and the National Association of Negro Musicians of which she was one of the most visible members. Her work was reviewed by the African American newspapers, including one of the most influential ones, the Chicago Defender. Price would often attend Black salons and social events held at the home of Estella Bonds, mother to composer and pianist, Margaret Bonds, or at the Parkway Community house. She lived for a time in the Bonds’ home and took an active role in mentoring the young Margaret Bonds and her compositional career. Price became acquainted with the already famous Langston Hughes at one of the many Black artistic events in Chicago. In setting some of his poems to music, Price used the work of the well-known poet to play with ideas of double consciousness in the African American experience. Double consciousness is a term coined by W.E.B. Dubois to show the tension of reconciling an African heritage through the frame of a White colonial racist society. In the selection of songs below, “Hold Fast to Dreams” and “Song to the Dark Virgin” are based on Langston Hughes’ poems.

Price’s identity as a woman also influenced her professional connections. As an African American with lighter skin, Price was afforded the opportunity to be involved with White women’s social networks to which darker skinned peers may not have been permitted. The Musicians Club of Women and the Chicago Club of Women Organists were organizations to bolster support for female musicians because they were being excluded by men. The organizations held social events and salons that led to Price’s work being heard by more members of the musical scene.

Legacy

Price’s reputation as a composer spread nationally and internationally until her death in 1953. In 2009, a couple in Illinois found unpublished manuscripts in her old house, and in 2019, her publisher Schirmer found additional manuscripts presumed lost. Writers have credited this as a “rediscovery” of Price and her music. The narrative discredits the work of historians such as Rae Linda Brown, however, who consistently researched Price and her music. Certainly, Price’s music has not traditionally been included in the classical-music canon, but her work never really disappeared. This module offers a way to view Price’s background with regard to the social structures that both limited, and helped to spread, her work. Many of Price’s songs have been published and they cover a range of topics for a variety of voice types. Still more songs may see the day, even though they remain so far in manuscript form.

Primary Sources

Price, Florence, and Richard Earl Heard. 44 Art Songs and Spirituals. Fayetteville, AR: ClarNan Editions, 2015.

“Civic Group Entertains Two Noted Women Composers.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition), August 24, 1946.

“Local Artist to Honor Florence B. Price.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition), April 3, 1948.

“Musical Works by Members on Club Program.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), February 6, 1949.

Secondary Sources

Brown, Rae Linda. The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price. Champaign-Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020.

Jones, Alisha Lola. NPR.org. “Lift Every Voice: Marian Anderson, Florence B. Price and The Sound Of Black Sisterhood.” Published August 30, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/08/30/748757267/lift-every-voice-marian-anderson-florence-b-price-and-the-sound-of-black-sisterh

Peters, Penelope. “Deep Rivers: Selected Songs of Florence Price and Margaret Bonds.” Canadian University Music Review 16, no. 1 (1995): 74-95. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/cumr/1900-v1-n1-cumr0466/1014417ar.pdf

Ross, Alex. “The Rediscovery of Florence Price.” The New Yorker. Published January 29, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/02/05/the-rediscovery-of-florence-price.

Thurman, Kira. “Performing Lieder, Hearing Race: Debating Blackness, Whiteness, and German Identity in Interwar Central Europe.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 72 no. 3 (2019): 825—865.

Walwyn, Karen. Florence Price. http://www.florenceprice.org/

Investigations

Listening

“My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord” (1937), performed by Marian Anderson and Franz Rupp.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z02yZIoPPlI

Listen for how Anderson enunciates the text. In the score, the last note has an option to go higher in pitch which is presumed to have been written to showcase Anderson’s vocal range.

“Hold Fast to Dreams” (1945), performed by Louise Toppin and Lydia Qiu.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFoEWPGsrvk

This song uses the text from a Langston Hughes poem “Dreams.” Listen for how the text and music accentuate one another. The piano at the end shifts through different harmonic registers leading up to a dramatic flourish which performers have described as characteristic for Price.

“Song to the Dark Virgin” (1941), performed by Darryl Taylor and Maria Corley.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=18-JLvwT0-4

Based on another Langston Hughes poem, this song presents some moments of text painting in which words like jewel and dark are accompanied by a change in the harmony to emphasize their meaning.

Critical Thinking

1) Learn more about some of the major figures in different arts disciplines of the Chicago Renaissance. What might be some of the reasons why the Harlem Renaissance is significantly better known than the Chicago Renaissance? In your research, compare Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem “truth” to Langston Hughes “Dreams.” Hughes said about the Chicago poet “the people and poems in Gwendolyn Brooks’ book are alive, reaching, and very much of today.” You can read more about her and read selected poems on the Poetry Foundation Website.

2) How does Price deploy such musical elements as melody, texture, range, rhythm, and dynamics (among others) to interpret the text of Hughes’ poems in “Hold Fast to Dreams” and “Song to the Dark Virgin”? How might the concept of double consciousness be applied to analyze these songs?

3) Using Price’s career as an example, explore how other composers’ artistic and social lives influenced their work. Consider the composers in the other modules, Dvořak and Saint-Saëns, or maybe more contemporary examples such as Courtney Bryan or Sarah Kirkland Snider. How were other composers affected by their social networks and by societal power structures? In what ways might this be reflected in their music, or might they deliberately resist such an entanglement of biography and creation?