Module 1: Animals as Others and Others as Animals

Module Introduction

Module Introduction

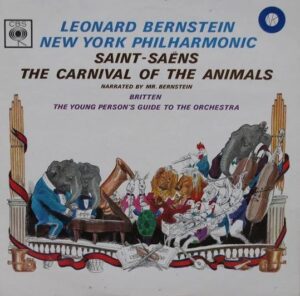

As explained in the Introduction to this unit, Saint-Saëns mocked his critics with Carnival of the Animals, portraying them variously as skittish chickens, lumbering tortoises, and braying asses. Criticizing people by comparing them to animals is both an old and a current cultural practice—see, for example, the sloths that work at the DMV in Disney’s Zootopia (2016)—but it has not always just been music critics or irritatingly slow administrators who have been the objects of this derision. Historically, people of minority racial, gender, or socio-cultural groups have often been derogatorily compared to animals, arising from the fact that at one time they were not considered fully human. Societally ingrained and legally sanctioned notions that some people are inferior made animal comparisons an easy reach. Another group of people who are often associated with animals are children, and this is perhaps why the Carnival of the Animals has come to be thought of as a children’s piece, though it was not composed for this purpose. When animals are used to represent racial minorities, women, and children, it situates them as Others different from an ideal of humanity that is grown, able-bodied, White, and male. Everyone else is treated as an improperly—or not yet fully—formed person.

Animals in Children’s Music

Cultural products aimed at children convey societal expectations for those children, ones that they must grow into. Dolls impart a physical ideal, stories have morals, and children’s music suggests appropriate cultural values a child should come to appreciate. These values might include the innocuous themes of friendship and board-approved expressions of individuality embodied by Disney Channel pop stars, or they might be the high-culture ideals of classical music through which children will supposedly become more sophisticated and intelligent adults. As Schumann scholar Roe-Min Kok points out, children’s music, marketed to parents who most wish to groom their children according to these ideals, can be very lucrative. But to be effective children’s pieces, they must appeal to children to some extent, and animals are often used to garner this appeal. Many of the most famous classical pieces for children include animal themes: Sergey Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf (1936), Maurice Ravel’s Mother Goose (1910), or “Jimbo’s Lullaby” (based on an elephant kept in Paris) from Claude Debussy’s Children’s Corner (1908). Pieces such as Peter and the Wolf, or the collection Animal Folk Songs for Children (1950) arranged by Ruth Crawford Seeger, are examples of music performing “social work” on children—in Prokofiev’s case promoting Bolshevik ideals of overthrowing old ways of thinking and overcoming nature, in Crawford Seeger’s of kindling a sense of unified national heritage.

The Unknowable Other: Woman

Foundational feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir asserted that men’s failure to recognize autonomous female personhood results in making women the default Other in society. In her book, The Second Sex, she further reveals a common desire among men to think of a woman as a domestic animal or piece of flesh for consumption. Her revelation helps to explain a curious convention of language: men (and sometimes women) often compare sexually enticing women to pussycats, vixens, or bunnies, elegant women to swans, sweet women to lambs, and those who are objects of contempt to cows, heifers, pigs, snakes, old bats, and bitches. The children’s folk song “I Bought Me a Cat,” which was arranged by Aaron Copland in Old American Songs (1950-52), tells of a farmer who buys a series of animals, feeds them, listens to the sounds they make, and is pleased by them. In the best-known version, his final acquisition is a wife whom he feeds like the animals of previous verses, and whose voice joins the parade of farm animals that recite their cries to end the song.

Animal Allegories

In Western media, talking or anthropomorphic animals are often used to euphemize the sensitive issues of race for children. Consider a movie like Warner Brothers’ Cats Don’t Dance (1997), in which humans oppress upright-walking, talking, and dancing animal actors to keep them from being cast in meaningful roles in movies and restrain them to only playing animal parts. Somehow, Warner Brothers missed the issue inherent to a metaphor about minorities who are represented by animals, but their oppressors get to be human. Disney’s Zootopia is a more recent example of a racism allegory in a children’s film, in which a world full of sentient animals are socially divided according to predators and prey. However, sometimes animals are used to avoid the issue of race rather than approach it. In Disney’s The Princess and the Frog (2009), Black characters Tiana and Prince Naveen avoid much of the racism one might expect the couple to encounter in the setting of 1920s Louisiana, because they spend almost the entire movie as singing amphibians—out in the bayou away from human civilization.

Primary Sources

Copland, Aaron. Old American Songs. New York: Boosey & Hawkes, 1997.

Debussy, Claude. Children’s Corner: For Piano. Edited by Wilhelm Ohmen. New York: Schott Music, 2009.

Prokofiev. Sergey. Peter and the Wolf: Symphonic Tale for Children, Op. 67. New York: Leeds Music, 1946.

Ravel, Maurice. Mother Goose: 5 Children’s Pieces. Edited by Lawrence Rosen. New York: G. Schirmer, 1995.

Saint-Saëns, Camille. Le Carnaval des Animaux. 1886. Facsimile of the manuscript, with an introduction by Marie-Gabrielle Soret. Paris: BnF Editions, 2018.

———. Outspoken Essays on Music. Translated by Fred Rothwell. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1922.

Schumann, Robert. Album für die Jugend, Op. 68. Edited by Klaus Rönnau. Vienna: Wiener Urtext Edition, 1979.

Seeger, Ruth Crawford, arr. Animal Folk Songs for Children: Traditional American Songs. Hamden, CT: Linnet Books, 1993.

Secondary Sources

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. Translated by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier with an introduction by Judith Thurman. New York: Vintage Books, 2011.

Kok, Roe-Min. “Negotiating Children’s Music: New Evidence for Schumann’s ‘Charming’ Late Style.” Acta Musicologica 80 no. 1 (2008): 99-128.

Morrison, Simon. The People’s Artist: Prokofiev’s Soviet Years. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Mundy, Rachel. “Animals on Parade: Collecting Sounds for l’histoire naturelle of Modern Music.” In The Modernist Bestiary: Translating Animals and the Arts Through Guillaume Apollinaire, Roaul Dufy, and Graham Sutherland, edited by Sarah Kay and Timothy Mathews. London: UCL Press, 2020.

Investigations

Critical Thinking:

How and when do children appear in art for children? Often media targeted at children does not include young children among the characters, which are instead older adolescents, young adults, or animals. When they do appear, how are they portrayed?

Listening:

Listen to Debussy’s Children’s Corner and research the piece, paying particular attention to the characters and musical material of no. 2 “Jimbo’s Lullaby,” no. 3 “Serenade for the Doll,” and no. 6 “Golliwogg’s Cakewalk.” These three movements evoke cultural products from places outside of Europe, namely Indian menageries, Chinese porcelain, and American minstrel theater, which were exotic fascinations for nineteenth and early twentieth-century Europeans. Discuss how a piece such as this teaches children to hear difference and to understand their own Self.