by Catherine Zachary

The 2018-2019 academic year was just the second to host UNC Library’s new Incubator Awards: Research Grants for Creative Artists. Applications are filed in September, awards granted in October, and presentations are made at the Incubator Awards Showcase in the spring. As their website puts it,

The Incubator Awards provide financial and research support for students using historical and rare library materials at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill towards projects in the arts. Students are encouraged to follow their curiosity and use archival and special collections items as source material and/or inspiration; projects do not need to rely exclusively on materials in our collections. Recipients will receive a small stipend, instruction in special collections research practices, and support from library staff as they conduct their artistic research. The Incubator Awards aim to foster engagement with UNC’s rich cultural and historical resources and encourage students to pursue new directions, topics, or methods in their work and creative process.

These awards have consistently produced engaging and innovative projects by grant recipients. Rising senior and music major, Anne Bennett, was a recipient in the 2017-2018 academic year and created five jazz compositions that explore the link between jazz and slavery (using archival materials from the Wilson Library Special Collections Library on jazz music and its pre-Reconstruction era roots). This year, music students Barron Northrup and Corbin Bryan teamed up to build a rare and near-forgotten instrument called the octochordon, an ancestor of the viola da gamba and the modern-day cello, using a book from the Rare Book Collection in Wilson Library.

After constructing the octochordon, Barron and Corbin presented it at the UNC Baroque Ensemble and Consort of Viols spring concert on April 28 and at the Incubator Awards Showcase on May 1. In late July, they will fly out to Portland, Oregon for the national conference of the Viola da Gamba Society of America to give another presentation and demonstration of their research and instrument.

To learn more about this incredible project, I reached out to Barron Northrup and Professor Brent Wissick, who served as the faculty advisor for the project.

Catherine Zachary: Tell me a little bit about yourself and the ways you’ve been involved in music during your time at Carolina?

Barron Northrup: I am a member of the class of 2020, double majoring in Studio Art and Communication Studies with a minor in Music. Aside from the Consort of Viols, my ensemble experience at Carolina includes one semester of Carolina Choir (Fall 2017). I began taking viol lessons informally during my first semester (Fall 2016), and the next semester I played in a small beginner consort that Professor Wissick dubbed the “Nova Viols.” We played one or two songs during the Viol Consort’s concert. The semester after that (Fall 2017) I joined the Viol Consort, so this has been my fourth semester in the consort proper.

CZ: How did you learn about the octochordon and what inspired you to team up with Corbin Bryan and apply for the Incubator Award to build one?

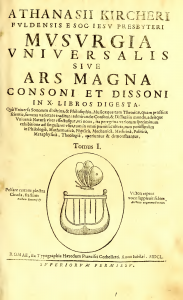

BN: The 2018-19 academic year marked the second time that the Rare Book Collection in Wilson Library held their Incubator Awards competition. I already knew of it; I attended their inaugural open house in the Fall of 2017, in which they displayed several interesting books and other collection materials as examples of potential inspirations for grant projects. One such book was Musurgia Universalis by Athanasius Kircher, which initially captivated me because it contained a plate illustration of several stringed instruments, including a viol. I did not apply for the grant that year, but the memory of the book stuck with me. Later that year I grew interested in musical instrument construction, and I thought again of that old viol illustration. I knew the Incubator Awards would occur again the following year, and I considered that I could use the grant to build an instrument if I could base the project on that book.

At this point, I had not yet reached out to Corbin. We didn’t know each other very well yet, but he had started attending consort meetings and learning to play the viol. He took the first-year seminar class in Music and Physics, in which Professor Wissick (director of the Baroque Ensemble and Viol Consort, and our faculty advisor) taught about the viol. Corbin had mentioned his fascination with the viol, and I knew that the Incubator Award could be undertaken as a team as well as alone, and so I asked him to join me – it wasn’t hard to convince him!

CZ: Local instrument builder John Pringle helped guide you through the building process. How did you learn of him and convince him to get involved with the project? And what was the process of building the instrument like?

BN: We already knew that building a musical instrument with no experience would prove a monumental task. However, we also knew from Professor Wissick that John Pringle, a master craftsman of musical instruments, lived a short drive away. He met with us and generously granted that if we could win the Incubator Award, he would be willing to work with us and teach us, and allow us to use his shop and tools. We sought to learn more about the octochordon, which proved to be quite an adventure.

As the title suggests, Musurgia Universalis is written in Latin, which neither of us read. But we found an English translation of the chapter on musical instruments in Davis library, which someone had translated for a master’s thesis. The section on viols was merely a paragraph but ended by mentioning that an English lord had invented an eight-stringed viol. We found this curious and searched for more information as the spring 2018 semester came to a close. We could find no historical record of an English nobleman known for inventing any instruments.

Furthermore, “octochordon” returned few results when input into an internet search engine, but one of those few results was an article written by a Canadian researcher named Stephen Morris about the English expatriate William Young, a contemporary of Kircher. Morris provided a translated correspondence revealing that Young wrote Kircher a letter shortly after the publication of Musurgia Universalis, politely but firmly claiming credit for the octochordon’s invention. Kircher replied, apologizing profusely for the misattribution. In this article, Morris remarked that the octochordon would be worth further research, so early last summer I found his email and reached out to him. He was quick to reply and proved very helpful in conducting further research.

Corbin and I were generously granted an Incubator Award in late Fall 2018, by which time we had completed most of our background research. The grant also included the special support of the library researchers, from whom we learned to examine our sourcebook as a historical artifact with data beyond what was written in the book. We visited John Pringle’s workshop once or twice a week for 2-3 hours each time to construct the viol. Because the process is long and complicated, he would occasionally instruct us to start certain tasks but then would finish them himself later, or would begin processes before we arrived and instruct us on how to pick up where he let off. In this way, he exposed us to a broad array of the necessary skills in violbuilding despite our limited schedule.

CZ: How has it felt being able to share this rare instrument with concert-goers and visitors at the Incubator Awards showcase this past spring?

BN: Sharing our research was very rewarding, both at the Incubator Awards showcase and at our viol concert at the end of the semester. After both presentations, we invited the audience to come and try the instrument out. Many people have never heard of the viol, much less held one, so it was a very special opportunity to introduce people to a piece of music history in a uniquely unforgettable way. Furthermore, ours is the only octochordon reconstruction in the world as far as we know, so it’s very encouraging to be able to contribute to musical research in a meaningful way – I never could have predicted this part of my undergraduate career.

But our research is ongoing: our next step will be to present at this years’ Viola da Gamba Society of America (VdGSA)’s annual summer conference, which I will be able to attend thanks to the generous Mildred Brown Mayo Undergraduate Research Fund in Music, offered through the Department of Music. This presentation will be unlike our previous two, because everyone in attendance will be familiar with the viol, and many of them are very knowledgable about its history. I’m excited not only for another opportunity to share our research, but also for the consequent conversations with professional musicians and historians, from whom I know I will gain even more pertinent knowledge.

CZ: What have you liked most about this collaboration with Corbin, Professor Wissick, and Mr. Pringle?

BN: Throughout this semester, Professor Wissick and John Pringle have been the very best of mentors and friends. Both are brilliant masters of their craft, but they are willing to sacrifice their time for the sake of beginners, namely Corbin and me. They have had patience for our learning curves and have always been encouraging. While I am certain that we will remain in contact, I will miss working with them as regularly as the Incubator Awards allowed us to.

As a Studio Art major and Music minor, I love to find the beautiful ways in which visual and musical arts interact, so this project has been particularly special to me for its integration of musical performance, organology, and history with elements of woodworking, sculpture, and design. My next project bridging art and music will take a wildly different approach: through the generous support of Arts Everywhere, I will be working with the UNC Symphony Orchestra to produce a photo portrait series. I am very grateful for the Department of Music’s support throughout the Incubator Awards this semester, and I am privileged to be able to continue our collaboration next year.

Professor Brent Wissick served as faculty advisor for the project and shared some insight on what the project was like from his perspective.

CZ: What was your first impression when Barron and Corbin came to you with the idea to apply for an Incubator Award to build an octochordon?

BW: Every professor delights in the moments when a student is grabbed by real curiosity and takes genuine initiative. When Barron and Corbin told me they had come across this path for research that was both historical and artistic, I was as excited as they were. Both had come to this study of the viola da gamba as a sort of accident. Barron came to me as a first-year because he wanted to learn cello to strengthen his work as a composer. I could not take him as a beginning cellist but could get him started on the gamba. He did have a background singing renaissance music in high school, so already had a headstart thinking about music as part of history. Corbin already played traditional music on the guitar but had not studied classical music. But he was a good science student, who first heard me demonstrate a gamba in the First Year Seminar I team-teach with Laurie McNeil in Physics that connects Music and Physics. He asked me if he could learn to play, and if he could ever learn to build a gamba. Between them, their interests in history, music, science, design and practical skills in woodwork allowed for a perfect collaboration. Plus, they are two of smartest, most positive and hard-working young people I know.

CZ: What was it like to watch them go through the process of building this instrument?

BW: Professors also know that any project will have moments when it is easy to be frustrated and discouraged. I discussed progress with these two regularly, and also kept in touch with Pringle on how they were doing. I even got to see cell phone photos of the progress. My sense is that they kept their eye on the goal, and maintained a schedule of disciplined work; impressive with all the other things they do. And how exciting to see the finished product.

CZ: How does it feel to play the octochordon, having seen the whole building process and knowing that it’s the only one in the world?

BW: I have played many gambas in my 45 years of playing the instrument. This instrument is not only lovely to behold, but feels good to play and sounds beautiful. And of course, it is remarkable that two undergrads imagined and led the way on this. John Pringle is one of the most distinguished senior builders of renaissance and baroque string instruments, whose career started in London over 40 years ago. (I am pleased to own a viol he made for me.) He has combined his background in research with practical and artistic skills for all of these years and like me, is really excited and moved to see two young people “carrying the torch” with such imagination and intelligence.

CZ: What are you most excited about the presentation at the Viola da Gamba Society of America this summer?

BW: The National Conclave of the Viola da Gamba Society of America will meet near Portland, Oregon this July. We expect over 200 people, a mix of professional performers and teachers, amateur players and builders. People of many ages attend, and Barron was one of many college students who were there last year. They applied to present their research, and have been assigned to a session that will also feature a senior scholar/performer who spearheaded research on an unusual gamba 40 years ago. John Pringle built the first modern example of this instrument back in London around 1979, and she will reflect on all the work that she and others have done with it since then. It is most appropriate that Barron and Corbin will have the honor and joy of sharing their work just before her remarks. I am so proud of them and pleased that the Incubator Awards and our department have been able to support their imaginative and innovative work.

UPDATE: Barron and Corbin traveled to the Viola da Gamba Society of America conclave this summer and were a huge hit! Reflecting on this experience, Barron said,

With the generous assistance of UNC’s Department of Music, I was able to attend Conclave this summer and present the octochordon again with Corbin. Sharing this project on UNC’s campus was rewarding, but it was a special treat to present to a community of gambists. In a wonderful reversal, I was no longer introducing an audience to something new; instead the octochordon became part of a larger conversation regarding the viol, its construction, and its more eccentric family members, notably the lirone that Erin Headley presented. It was most rewarding to speak with her and several others who pointed me toward other quirky historical instruments, or art and iconography, that might provide another lead in learning more about the octochordon.

More information about the Incubator Awards can be found at https://library.unc.edu/incubator-awards/. And more information about the 57th Annual Viola da Gamba Society of America Conclave can be found at https://vdgsa.org/cgi-bin/conclave-2019/2019conclave.cgi.