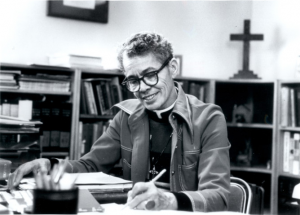

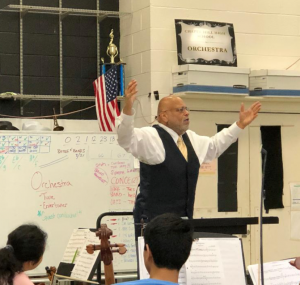

Later this month, the UNC Symphony Orchestra, directed and conducted by Tonu Kalam, will be premiering a new work, titled Dark Testament, by conductor and composer, William Henry Curry. Curry is the current conductor and music director of the Durham Symphony Orchestra and has been the resident conductor for the North Carolina Symphony, New Orleans Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Indianapolis Symphony, and has guest conducted with major opera houses, ballet companies, and symphony orchestras across the country and globe.

Later this month, the UNC Symphony Orchestra, directed and conducted by Tonu Kalam, will be premiering a new work, titled Dark Testament, by conductor and composer, William Henry Curry. Curry is the current conductor and music director of the Durham Symphony Orchestra and has been the resident conductor for the North Carolina Symphony, New Orleans Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Indianapolis Symphony, and has guest conducted with major opera houses, ballet companies, and symphony orchestras across the country and globe.

Curry’s new piece, Dark Testament, pays tribute to three African American, trailblazing women: Mahalia Jackson, Pauli Murray, and Harriet Tubman. UNC Symphony Orchestra director Tonu Kalam, along with support from Arts Everywhere, commissioned Curry to write a piece for the group last summer. Kalam chose to commission the piece from Curry because of their longstanding friendship and his admiration of Curry’s musicianship, and said, “He has so much to offer as a musician and as a human being.”

While Kalam commissioned Curry to write the piece, he didn’t specify anything about the piece’s content. That came solely from Curry. And as Curry puts it, he doesn’t compose a new piece unless he feels that he truly has something to say.

After cancellations in the fall performance schedule due to COVID-19, Dark Testament will see its world premiere at the April 28 concert. Below, Curry explains more about why Dark Testament needed to be in this world. This interview has been condensed for time.

UNC Music: Tell us a little about yourself and your musical journey as a composer and conductor.

WHC: Well, I grew up in a lower middle-class home in Pittsbugh. I think we could have been classified lower-middle class, but it’s probably something less than that. We couldn’t afford a TV until I was five years old, this is when something Iike 87% of United States population had TVs, so it gives you an idea. But like many, many people in my generation and hopefully succeeding generations, we got everything we had to have and we were loved. Me and my little brother went to an all-Black elementary school, which was totally under-served. There were no music programs, no art programs; we were completely out there forgotten, of course, being an all-Black elementary school in the early 1960s.

My life changed when on a family trip to Virginia. We were in the car and I looked over to the side of the road, I can still see it, I was nine then, and I saw ‘colored’ and ‘white’ drinking fountains and I didn’t know what that was. I looked at my mom and asked, in all innocence, “Is the water in that fountain colored?” I don’t remember exactly what she said, but she did say that’s their problem, not yours. Think of how difficult it is for a parent to explain a complicated matter like that. But the one thing I remember is that day saying “This is so insulting and white people are actually in charge of this. Not Black people, not in 1963. How dare they? Why didn’t they handle this?”

When I went back to school that fall, [and got to] “and liberty and justice for all” in the Pledge of Allegiance, I refused to say that. “Justice for all,” I’m not going to say that. So, of course, I was thrown out of school, an early civil rights activist. And the administration said you’re not going back to school until you say the Pledge of Allegiance with the class. So my mom said, “When you get to the ‘justice for all’ part just curse.” So, that was so eye-opening, and this is a time when the “great white father” Ronald Reagan said America didn’t have a race problem. And here I am at nine saying, “Wait a minute here, the entire deck is stacked against me.” There were no Black people on TV, no Blacks in TV commercials.

So my salvation was when a Jewish gentleman noticed somehow that this Black school over here didn’t have anything. He donated his own string instruments, and his lessons, and his time for these Black kids. My little brother and I were both in this first class with Eugene Reichenfeld.

My brother has been in the Cleveland Orchestra as a cellist for 41 years, and between us, we have performed in every major Concert Hall in the entire world. How did this happen? Because one Jewish gentleman, a minority himself, said, “Wait a minute, there’s something wrong here.”

And the fact that two boys out of the same family did that well in the classical music world is kind of a miracle, or maybe it’s not a miracle, but we were lucky to have that chance. Fortunately, I was a complete intellectual nerd. I mean my idea of a good time was trying to memorize the encyclopedia, that to me was fun. So the idea of instruments and classical music and Beethoven and Shakespeare and Tennessee Williams, all that greatly appealed to me.

Eugene Reichenfeld, who was my teacher, saw that I was inhaling classical music. He loaned me records and conducted scores, and one day after my lesson, he said, “I think you would make a good conductor.” And I said, “How did you know that’s my secret ambition?” Because I was extremely shy, extremely introverted, but he somehow knew there was some kind of infectious love for music. And he let me conduct his orchestra the next week, but I said to him that night, “Look, I don’t know how to conduct.” He said, “Conductors are born and not made.” Now, it took me 20 years to realize what that meant. He told me to get on the podium and teach myself. If something works, don’t do that again – find another way with a different gesture to get the same thing so it’s not always the same monochromatic gestural style.

I made my conducting debut when I was 15. I was also composing for a theater group or Shakespearean theater group at the Carnegie Library in Pittsburgh. So I look back on this, and I say “wow.” I mean, you know, I was saved by my incredible curiosity for history and books, plays, and music above all. All different kinds of music: Broadway, Hollywood, Motown, the Beatles, etc. So I entered the Oberlin Conservatory. And at that time, I decided to give up composing because I didn’t want to be a jack of all trades, master of none.

By the time we get to 1980, I’m the resident conductor with the Baltimore Symphony. I’m 26, and Aaron Copland is guest conducting in his birthday 80th year. And so, of course, I go up to him and we had a 45-minute conversation. I said, “Mr. Copland my secret dream is to also be a composer.” And Copland was one of these angels that treated everyone like equals, didn’t matter whether you were a kid, he took you seriously. So, with his warmth and wisdom in this 45 minutes, he said to me, “As a conductor, you’re in competition with every conductor. As a composer, you’re in competition with the living and the dead. Which is true, I mean think of a concert program, “Shall we do Beethoven or Curry? Shall we do Tchaikovsky or Curry?” So, in other words, can anything be more competitive than having to deal with 400 years of great geniuses that have come before you? It did not make me want to compose. But it did instill in me, if you’re going to do this, you don’t scribble on a piece of paper and expect someone other than your mommy to put a gold star on your head. It’s got to be wonderful or, at the very least, you’ve got to give it everything you have. So that was an invaluable lesson, but I didn’t go back to composing until the late 1980s.

I began to write these pieces for orchestra, and like I say there’s nothing more difficult because people are comparing you to Mozart. Before my first world premiere, I just couldn’t sleep at all for weeks. I conducted the premiere with the Indianapolis Symphony and afterward, a person in the orchestra said, “Bill, you couldn’t see the audience at the end, but they were giving you a standing ovation before the piece was over, if you can imagine that.”

UNC Music: What made you say yes to this commission project? What are you most excited about with this commission?

WHC: I was very flattered because I respect Maestro Kalam greatly, and was honored that the university commissioned me formally to do this. For me, I will only write a piece if it has to exist in this world. I’ve turned down no less than $12,000 in commission money because I don’t want to write that piece. That piece does not have to be brought into the world. So there’s always going to be some kind of extra-musical reason for me to write a piece, it has to be from the heart, because I rely on inspiration, though it’s only 10% of it, just like Edison said.

This piece, I felt had to come into the world. It was a combination of ideas floating all around the room in my brain, and it all came together where I could discuss in musical terms, even though it’s an abstract piece, some of the issues that most concern me these days.

UNC Music: ‘Dark Testament’ pays tribute to Mahalia Jackson, Pauli Murray, and Harriet Tubman. What inspired you to write about these three women in particular?

WHC: During her era, Mahalia Jackson was a big, big deal, not only to Blacks but also to whites. Mahalia Jackson, the Queen of Gospel, before Aretha Franklin there was Mahalia Jackson a household name, can’t get any bigger. I invite you to read her Wikipedia entry… It was bad enough, being a Black man then, but if you were a woman, good night nurse. Where this strength came from… And so the idea came to write from reading about her and not wanting to see her lost, that the whole piece would be about African American women that were as strong as any people that ever existed.

So the idea of strong African American women is the basis of my piece. Mahalia Jackson is the tribute of the first movement, and I use the spiritual “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around,” no one is going to defeat me. No one is going to defeat me.

And then someone I only recently came across is Pauli Murray. She was born in Baltimore but grew up in Durham. I didn’t know until I started to write this piece based on “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” I didn’t know that she was a motherless child. So when I finished the piece, I said, well, maybe I should see about her parents. Then I found out her mom died when she was three and her dad was taken to an asylum shortly afterward and he was beaten to death by a guard in the asylum. So, “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” that’s Pauli Murray. The first African American Episcopal priest, a lawyer, a poet, civil rights and women’s activist, a lesbian, probably, she was a little fluid, some historians call her transgender now. Again, the era, 1910 to 1973… When I think of the difficulties I have had and the doors that have been shut to me, the glass ceilings that have damaged the top of my head, I think “Oh, my God. This woman had iron in every cell of her body.” And she wrote a book of poetry called Dark Testament, and so I call the entire piece Dark Testament.

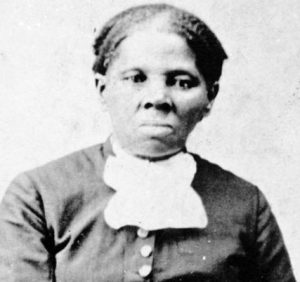

Then Harriet Tubman. Harriet Tubman was supposed to be on the 20-dollar bill by now, if you remember that Obama had put it in the works. Andrew Jackson has his problems, you know with the Trail of Tears and other things like being a slave owner, why not a black person? And if not Martin Luther King, Harriet Tubman. But reading about her, I feel embarrassed that I didn’t know more. This wasn’t part of my education growing up. The underground railroad now, as you know, it wasn’t a railroad in a literal sense. But I use my artistic license, as I think it’s called, and I write train rhythms and a part for steam engine whistle. And this is based on my own spirituals because I said, “well, let’s try to replenish the supply” with the idea that a spiritual is simple materials and a poignant, direct message about freedom, misery, hope, suffering, faith. So that movement is dedicated to Harriet Tubman, and that ends the piece.

UNC Music: What was the composition process like for this piece?

WHC: The process should’ve begun last August. Well, I didn’t. It didn’t because I couldn’t figure out a piece that I wanted to write. [Professor Kalam] asked me to write a piece for strings. But that’s too abstract, for me. For me, it had to have some kind of extra-musical connection that related to music in my own way. So I really told him about a month ago, “I’m sorry, Tonu, I can’t do this. It’s not going to happen, you have to substitute a piece for mine.” Because the first rehearsal is coming up in three or four weeks and I hadn’t had – didn’t have – a note. He said, “I’ll give you one more week.” And I said okay.

And then I pulled all these previous ideas together. You always have a light bulb over the head moment. Where you can see from the beginning of the piece to the end of the piece. You can’t describe it, but there are no roadblocks, you can see through the end of the piece, and I saw that. With a rockin’ Gospel beginning, and with a very poignant Pauli Murray, “Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,” the slower time, and then with this rockin’, rip-roaring, underground railroad with the train rhythms.

UNC Music: Do you have a favorite movement?

WHC: I mean, come on, every mother loves each child the same. Some may disappoint them, some may excite them, but I love all my children. But, if I were prodded towards answering you, I’m really, really, really, really, really happy with the third movement. I think this is really one of the best pieces I’ve ever written. Each piece is a learning experience.

UNC Music: What do you hope that students and audiences will learn from you and this work?

WHC: Well, I can tell you, I didn’t know these three Black women very well except by their reputations. You know, the two or three things you could say about them that energize me and maybe admire them greatly. But then I started to read about them and I said, “how did they do this?” What kind of people are we talking about? Because you’ve got to be your own best friend, and when someone takes you to the floor some people don’t get up. They say “I’m done. No one’s here to help me get up. If that’s the way it’s going to be, I’m just going to go elsewhere.” So these women are extremely important. I need heroes.

I don’t know whether everyone needs heroes, but I need heroes that do incredible things, and they’re human.

And as far as my own music, I don’t think I’ve said this for 30 years… If you’re not trying to write something as beautiful as George Gershwin’s song “Summertime”… At least for me, that’s what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to write something as beautiful as “Summertime” is. I think there’s never enough of that in the world, so I want this music to be poignant and wildly entertaining and vivid and colorful.

UNC Music: Is there anything else that you’d like people to know about yourself or this project?

WHC: Yes, I will say about conducting around the world, composing pieces, getting standing ovations, writing articles, performing viola concertos, teaching classes, and all … they say, “Well, that’s easy for you.” [Curry shakes his head.]

You are not going to do anything for 10,000 hours unless you love it. I mean you might be doing it for money or vanity, but I’m saying that I could never become a ballet dancer. I’m not going to practice 10,000 hours. So, when people see me get a standing ovation, they can do that too. They can also write a good piece; they just don’t do it. And I identify with the fear of the empty page and they say, “Oh, who am I kidding? I can’t do this.” We’re all that way, even the greats. Maybe, especially the greats. Because if Stephen Sondheim spends three weeks on one lyric, that’s not genius. As he would say, that’s hard work. That’s all, I spent three weeks on six lines. So, if there’s no partner or parent behind you, you have to say, “I’m going to do this. I’m going to do this and if I give it everything I have, then I’ll be proud of myself and God will be smiling because at least you gave it your all. And if no one likes it now you go back to the drawing board.” But no one should think that they can’t do something incredible without putting in the time. Yes, yes, yes, write the great American novel, write a book of poetry, go help people that are suffering in jail. Yes, you can do that, yes.

When I was in the hospital, two years ago with a busted out knee, these nurses… I interviewed them, they said no one had ever interviewed or thanked them for what they were doing. And I said, “Why are you here?” And they all said I really wanted to help other people, and these nurses were involved in nursing activities that aren’t so clean or sweet, but they came in every day, looking at me like I was the only person that ever lived. They’d care for 20 people in one half an hour, but these nurses made me believe that there’s no one more important in the world as important as me at that moment. And you know what? They were right.

Because at that moment, with our one-on-one interaction, there is nothing more important in the world. To be fully present in the moment. Between you and I, we can help each other in a sense. So yes, you can do whatever you want to do, but it’s all about being an earth angel, we must support each other.

I’ve been chasing Leonard Bernstein my entire life. He was my hero growing up – composer, conductor, performer. I have not reached his level now, but think of this, I had such a lofty example. How much further I went, because he was the model and nothing less will suffice.

Further Reading and Listening:

Learn more from William Henry Curry and his Monday Musical with the Maestro blog series! https://durhamsymphony.org/conductors-corner/. A couple of his favorites are:

“Journey into Jazz, Part II: Duke Ellington and Martin Luther King.” November 23, 2020. https://durhamsymphony.org/2020/11/23/monday-musicale-with-the-maestro-november-23-2020-journey-to-jazz-part-ii-duke-ellington-and-martin-luther-king/.

“Sharing the Spirit of Martin’s Dream.” January 18, 2021. https://durhamsymphony.org/2021/01/18/monday-musicale-with-the-maestro-january-18-2021-sharing-the-spirit-of-martins-dream/.